China and the US are Running a Different AI Race

End of the day, business strategies are market-driven

Hi All,

It was a pleasure working with and on this piece as a guest author for Exponential View last week. Azeem is a British technology entrepreneur and author. He founded the research group, Exponential View, and web technology company, PeerIndex.

He wrote "The Exponential Age: How Accelerating Technology Is Transforming Business, Politics, and Society" and hosts the podcast "Exponential View," distributed by Harvard Business Review, as well as the Bloomberg Originals television show and podcast "Exponentially with Azeem Azhar.” He writes about the topics of AI, renewable energy, and tech more broadly.

This piece delves deeper into the divergent strategies adopted by Chinese and US AI companies, driven by differences in their capital structures and existing internet ecosystems.

And like what Azeem wrote, “The US-China AI rivalry has become the defining geopolitical lens through which many view the future of technology. And for good reason: it’s shaping export controls, industrial policy, and innovation trajectories on both sides. However, when a single narrative becomes dominant, it can overshadow more nuanced analysis.”

See full post below.

China and the US are running a different AI race

On Wednesday, the White House published the AI Action Plan, a playbook for building an AI innovation ecosystem. It’s a bet on destiny that intelligence, once summoned, will reorder the world.

China isn’t chasing destiny. It’s deploying fast, frugal, open-weighted models and wiring them into the economy.

That pragmatism unnerves Washington. Chinese labs now ship foundation models faster and cheaper, and – crucially – they publish the weights. Silicon Valley reads this as “open the weights, kill the moats” – a threat to the revenues that depend on keeping the model layer proprietary.

Inside China, the logic is flipped. Once the models are treated as commodities, profit shifts to the application layer. Publishing the weights speeds that shift. Free forks and vertical fine-tunes multiply, each one funneling demand back to the riginator.

However, this isn’t some grand strategy being directed by the governments on both sides; it is market-driven, shaped by three structural forces – chips, capital, and distribution – that make open‑weight releases the logical on‑ramp to value.

Today, I will break down why I believe that China and the US are not running the same race and hopefully offer a different perspective.

Deployment vs Destiny

The real split is over where each country’s tech companies believe the profit will land. China bets on applications; America bets on the model itself. Palo Alto obsesses over model‑led destiny: ever‑bigger parameters, safety benchmarks, and a near‑cult-like obsession in the pursuit of AGI. As Karen Hao recounts in Empire of AI, Sam Altman and his peers see AGI as a world‑changing force capable of solving humanity’s most significant challenges. The wager is long, deep‑pocketed and proprietary: pour venture billions into loss‑making models today; own the platform that reorganizes industries tomorrow.

China’s approach is more pragmatic. Its origins are shaped by its hyper‑competitive consumer internet, which prizes deployment‑led productivity. Neither WeChat nor Douyin had a clear monetization strategy when they first launched. It is the mentality of Chinese internet players to capture market share first. By releasing model weights early, Chinese labs attract more developers and distributors, and if consumers become hooked, switching later becomes more costly.

Entrepreneurs then have the opportunity to utilize these models as free scaffolding. Taking the EV industry as an example, over twenty Chinese automakers, including BYD, Geely, and Great Wall Motors, have integrated DeepSeek into their in-car AI systems to enhance smart assistants and autonomous driving capabilities. In healthcare, it is said that nearly 100 hospitals across the country have now integrated DeepSeek for medical imaging analysis and clinical diagnosis support. Every new integration expands the model’s footprint, tightens switching costs, and shifts margins to the services sitting on top.

China’s so‑called “open‑source strategy” is a corporate pragmatism play, not a grand geopolitical scheme. But to see why pragmatism took this particular form, you need to see the three forces driving it – chips, capital, and distribution – turn openness into the default.

Chip Scarcity

America has had export controls on China since October 2022, preventing Chinese model makers from accessing the latest Nvidia GPUs. Overnight, the brute‑force “scale‑to‑AGI” playbook – whether China wanted it or not – was off the menu. Chinese labs were left with a patchwork of last-gen Nvidia GPUs and local chips, at least one to two years behind the US hardware frontier.

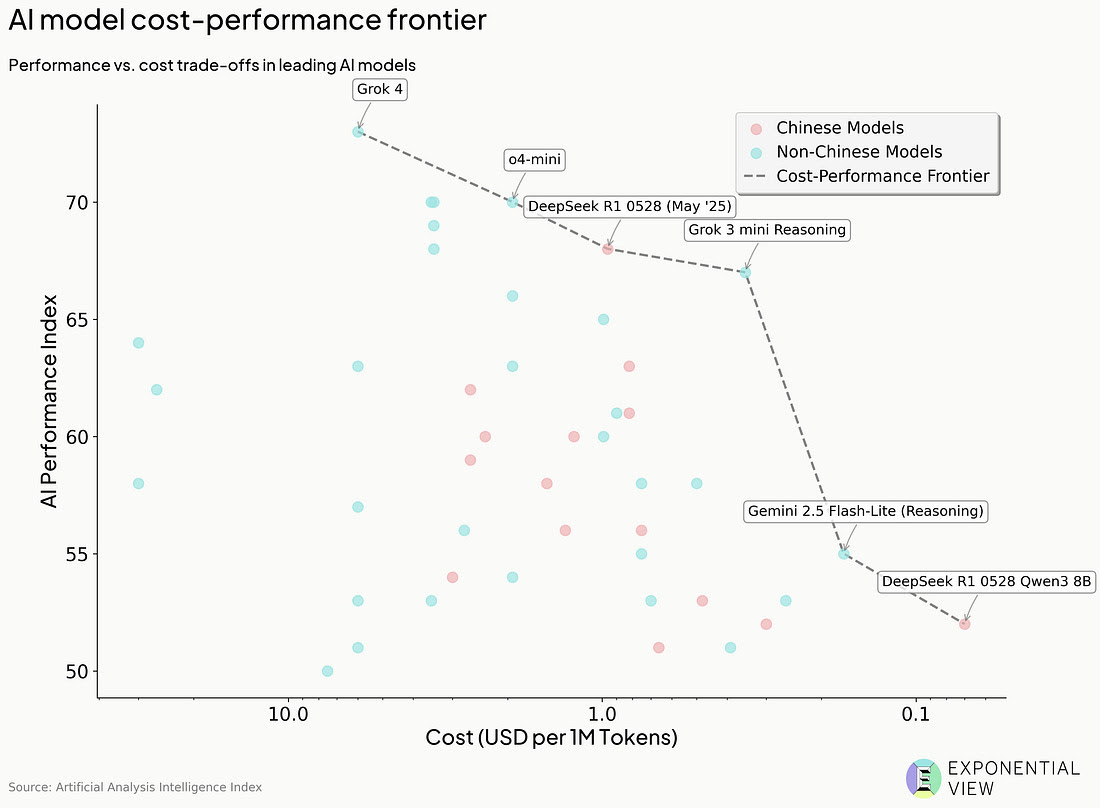

Because chip access is capped, efficiency has become the main event. Chinese researchers have been focusing on extracting the most from their hardware. DeepSeek‑V3 delivered GPT-4o performance at 18x cheaper cost, while Moonshot’s Kimi K2 used MuonClip, which likely halved the FLOPs used during a training run. America’s chip curbs have unintentionally turned China’s models into performance‑per‑yuan champions. As many have said, “necessity is the mother of invention.” Now, Chinese models are so competitive that both local and international companies want to build on them.

Capital Drought

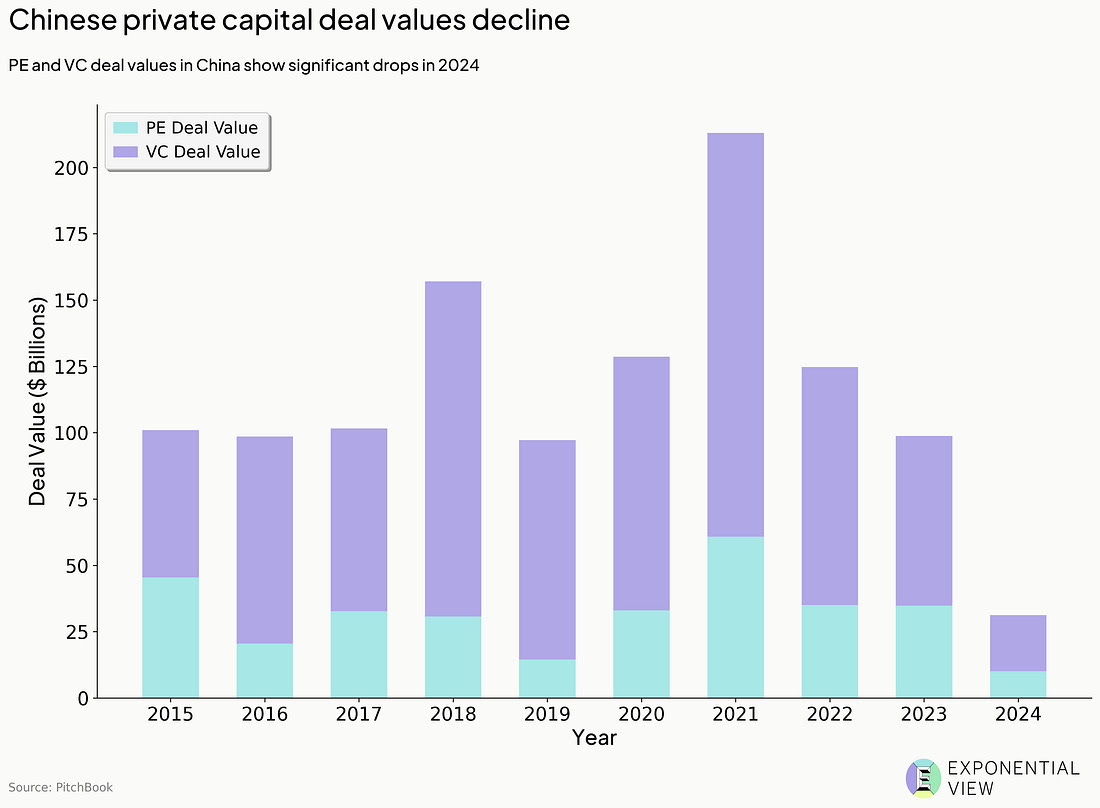

The same efficiency drive also aligns with corporate reality. With venture money scarce and a lingering urge to prove they’re innovators – not copy‑cats – Chinese founders must signal value fast.

The more the models are used, the bigger their moats and their name. This is an essential characteristic of Chinese AI, stemming from the fact that China’s funding environment is scarce compared to the US. US venture capital plowed $100 billion into AI in the first half of 2025. Meanwhile, Chinese startups across all sectors raised barely $11 billion from VCs. Since China’s leading ride‑hailing app DiDi delisted from the NYSE in 2022, a regulatory storm has swept across the country’s internet sector. Some American funds pulled out of China, and even Chinese ones became skittish. The US government implemented a rule that disallowed US investors from investing in AI and chips. Chinese start-ups in AI now, compared to ten years ago during the internet era boom, raise capital only after they can demonstrate a live product and real usage figures.

Chinese models may be efficient, but DeepSeek is still estimated to have spent over $500 million in total R&D for R1. Luckily, they were self-funded by hedge fund billionaire Liang Wengfeng. But how do the other startups get funding? If you look at the “four AI tigers” – Baichuan AI, Zhipu AI, Moonshot AI, and MiniMax – most had to secure backing from the BBAT quartet. For Baichuan and Zhipu, releasing strong open-weight checkpoints helped persuade Alibaba/Tencent that the teams could ship and attract a developer ecosystem, unlocking nine-figure cheques only after the code was dropped.

Distribution Choke-Points

Once a model maker has a reputation, what keeps them open-source?

Not every Chinese model is open‑weight – ByteDance’s Doubao 1.5 Pro keeps its parameters under lock and key – but most still publish. As mentioned earlier, this reflects the Chinese mobile-first digital economy. A typical Chinese digizen opens fewer than ten apps a month, almost all of which are funnelled through WeChat or Alipay; in the US, the figure is closer to thirty. Scale belongs to whoever can seed a model across those few choke‑points fastest. It’s led to some unorthodox decisions. Look at what Tencent did. The WeChat team wanted a good LLM fast. Yuanbao, Tencent’s AI division, wanted its proprietary engine showcased. The WeChat team went ahead and plugged in an external open-weight rival, DeepSeek R1, because it was better than anything Yuanbao had made. This is a typical move by Tencent, where product leaders trump company management in product deployment sway.

But that isn’t how Alibaba or ByteDance operates. Top company executives rallied top engineers to get their heads in the game. Beyond what is known as the 996 work culture, seven-day stints in the office to refine consumer-chatbot models are, to be honest, quite normal. In that environment, open-source software acts as growth hacks: zero licensing friction, instant plug-in, and viral forks. The BBATs want market share, and openness is the shortest route.

In truth, though, it’s not all just about corporate strategy either. It’s the chip on the shoulders of Chinese entrepreneurs that is driving their embrace of open-source, too. For decades, Chinese goods were called “copycatters.” Many AI founders and leading researchers are choosing to open-source their research to demonstrate to the world their innovation and capabilities. The psychological element shouldn’t be overlooked, as this open-source vs closed-source debate has long existed in the technology industry. For those who are pro-open, it means more scrutiny and potentially faster advancement of their research, as well as broader adoption. For those who are pro-closed, the argument is based on proprietary knowledge and protectionist thinking.

The Chinese Government doesn’t particularly care about the open-source strategy in itself. All they want is for AI to be in every pillar of its economy through its five-year plans. Instead, it’s the entrepreneurs’ philosophy, combined with structural drivers, that have pushed the open-source flywheel to the centre of the Chinese AI ecosystem.

[Though you can learn more about the government’s efforts on pushing forward AI and robotics through its “Made in China 2025” plan, “East Data West Compute” here. These top-down-led initiatives are mostly to drive 1) Accelerated Innovation and Self-Reliance; 2) Global Competitiveness; 3) Sectoral Transformation - manufacturing, transportation, healthcare, agriculture; 4) May have socio-economic impacts - bolster economics but may widen regional disparities.]

It’s Not a Race.

I want to reiterate that China and the US are not running the same race. Deployment is China’s dividend, and destiny is America’s dream. Each is chasing what it values most. Chinese companies integrate open-source models into daily life because speed-to-market incentives pay off fastest at the application layer. Silicon Valley pours capital into ever-larger proprietary models, hoping to reach AGI first, whatever that means at this point.

Chinese model makers are responding rationally to their environment. Chip constraints reward efficiency, while funding structures and market-share chasing dynamics push them toward open-source. Make no mistake, China’s current open‑source “strategy” is market‑driven, not state‑driven. It is pragmatic; as a Chinese saying goes, “兴趣不可以当饭吃,” literally meaning “interests can’t be eaten as food.” In China, even AI must earn its keep.

Appreciate the analysis, good post.

Excellent post. Thank you.