Why Data Centers Can’t Go Full Renewable—Yet

Limited dispatchability, Intermittent Supply and Costly Battery Solutions

We’re inundated with headlines proclaiming that “data centers are driving the renewable transition.” However, secretly (or not so subtly), major tech companies are backtracking on their carbon neutrality goals as they scramble to build more data centers to support their artificial intelligence development needs. The potential climate impact is palpable, and industry experts across the ecosystem are asking why data centers can’t be powered with renewable energy.

The Power Needed to Power AI

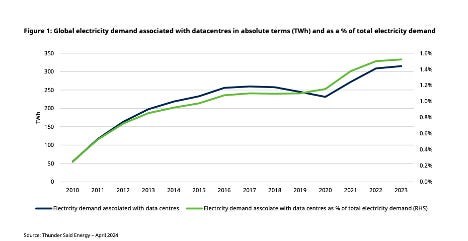

Niklas Sundberg of SustainableIT.org highlights that a single query on ChatGPT generates 100 times more carbon than a Google search. In the U.S., data centers could account for 8% of total electricity needs by 2030, up from just 3% in 2022, according to Goldman Sachs. Even before AI’s impact was felt, electricity demand from data centers grew at a compound annual growth rate (CAGR) of 14% from 2010 to 2023—far exceeding the global average growth rate of 2.5%, according to SemiAnalysis estimates. This surge is driven mainly by companies migrating data storage and compute power to the cloud and increasing computational needs due to data proliferation.

Even Sam Altman, CEO of OpenAI, highlighted that energy is “the hardest part” of meeting AI computing demands. Data centers consume 20 to 50 times more energy per square foot than commercial office buildings. This brings me back to the question: Why are we not using renewable energy to power data centers?

Given the intensity of power needed to power AI, hyperscalers like Google, Amazon, Meta, Microsoft, and Apple have made ambitious pledges to source renewable electricity and decarbonize. However, powering data centers with intermittent renewables is not feasible in the near term. According to a report from Schroders, these tech giants are circumventing the issue by signing virtual power purchase agreements (PPAs) with renewable developers. This means they buy renewable energy credits while still drawing electricity from the grid, including green and gray sources for their operations.

In layman's language, big tech uses whatever amount of power is required to power a data center directly from the grid. Then, it pays for or invests in another renewable power generator, which adds that renewable energy amount to the local grid from which it purchases electricity. Thus, it can“offset” its non-renewable footprint, otherwise known as greenwashing.

But it’s not like they’re not trying. The main challenges preventing data centers from solely relying on renewables are:

1) Limited Dispatchability: Solar and wind energy are inherently intermittent, which means that their output depends on weather conditions and the time of day, simply things we cannot control.

2) Inconsistency of Renewables: Data centers require a reliable, continuous power supply—something intermittent sources cannot guarantee.

3) Inadequate Storage Solutions: To effectively manage the renewable energy supply, current energy storage technologies need to be more sophisticated and cost-effective.

Solar and Wind are intermittent and non-dispatchable

Traditional solar photovoltaic (PV) systems and wind power are typically non-dispatchable, mostly because solar and wind energy are inherently intermittent. They depend on the availability of sunlight, which varies throughout the day and is affected by weather conditions. Thus, a grid operator cannot control solar and wind energy regarding when and how much electricity it can produce. However, data centers need reliable 24/7 power with effectively zero downtime, and any dips or interruptions cannot be tolerated.

Thus, Schroders noted that hydro and nuclear power would be much more ideal alternatives than solar and wind energy. They wouldn’t have the dispatchability and intermittent issues. Still, given the geographic constraints (you cannot control where there is a lake/ dam) for hydro and the overall public court of opinion against nuclear, right now, none of these renewable options are viable options in replacing traditional power sources. (I will dive deeper into the nuclear piece in Japan, where there have been debates on whether the island country should reactivate nuclear plants due to the data center demands.)

Expensive Energy Storage

Often, you’ll get oversupply generated during peak hours, such as around noon by solar and ultra-windy days when wind solutions go wasted that day. So why can’t we store the solar/ wind energy, then?

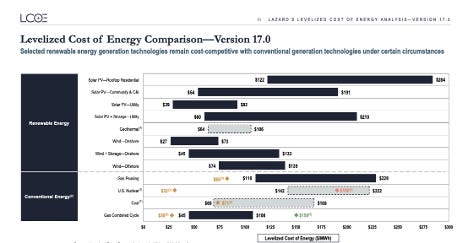

Well, energy storage solutions right now can be pretty expensive. Say you have 10 hours of bright sunlight; you’d need batteries that can run for 14 hours to power the rest of that day. Looking at it economically, gas in the U.S. and coal in China are much cheaper than solar energy + battery cost. So, for businesses to justify the switch to 100% renewables, it will need to be more than an ESG narrative.

See chart here from Lazard’s Levelized Cost of Energy Comparison (LCOE) 2024 Report.

Currently, batteries aren’t the most cost-effective way to preserve renewable energy for data centers. And even if we had batteries, how can we guarantee that we would produce enough renewable energy when the weather changes from season to season? For example, we’d have very little solar power during the winters, so we would need a backup solution using traditional energy sources when the dip happens.

Lithium batteries are light and quick to charge, which makes sense for phones and EVs. However, they might not be the best solution for data centers, which is why people are talking about long-range solutions—which I’ll explore further in another piece. Moreover, safety concerns surrounding lithium batteries have been highlighted following incidents like the tragic fire at a South Korean factory.

While the narrative around data centers driving the renewable transition is compelling, the current reality is far more complex. Companies, innovators, governments, and regulators must confront significant barriers before fully embracing renewable energy sources for their voracious appetite for power. Until then, we’re probably still heavily reliant on coal and gas.

Thank you for reading. If you find this insightful, please subscribe.