Why China’s AI Strategy Differs from that of the U.S.

Divergence in AI commercialization (Part 2): China excels in consumer platforms but struggles in enterprise software.

Hi everyone, as promised, this is Part Two of the collaboration series with

on the divergence of AI monetization strategies adopted by Chinese and U.S. big tech companies. In Part One of this series, we examined how AI commercialization by big tech in the U.S. is driven by enterprise applications, leveraging the country’s strong cloud computing industry. In contrast, China's leading tech companies’ approach prioritizes embedding AI into existing consumer platforms, resulting in a distinctly different path for AI’s diffusion. In Part Two, we’ll look at potential explanations behind this divergence.TL;DR

China and the U.S. are taking divergent paths in AI commercialization, reflecting fundamental differences in their digital ecosystems and even broader economic structures:

U.S. Focus: Enterprise software and cloud-based AI solutions

Leverages strong cloud computing industry

Caters to a developed knowledge economy with a high demand for productivity tools

China's Approach: Consumer-facing AI applications

Embeds AI into existing popular platforms (e.g., WeChat, Meituan)

Driven by intense competition for user engagement in the consumer internet sector

In this article, we focus on understanding the key factors behind China's weakness in enterprise software adoption and how that has affected China’s AI monetization strategy:

Industrial composition favoring labor-intensive sectors

Prevalence of state-owned enterprises with unique constraints

Availability of cheap labor, which reduces incentives for automation

Informal work processes and blurred work-life boundaries

The divergence may impact AI's broader economic effects:

In China, AI benefits may remain concentrated among tech giants

In the U.S., wider adoption through enterprise services, but productivity gains are still uncertain

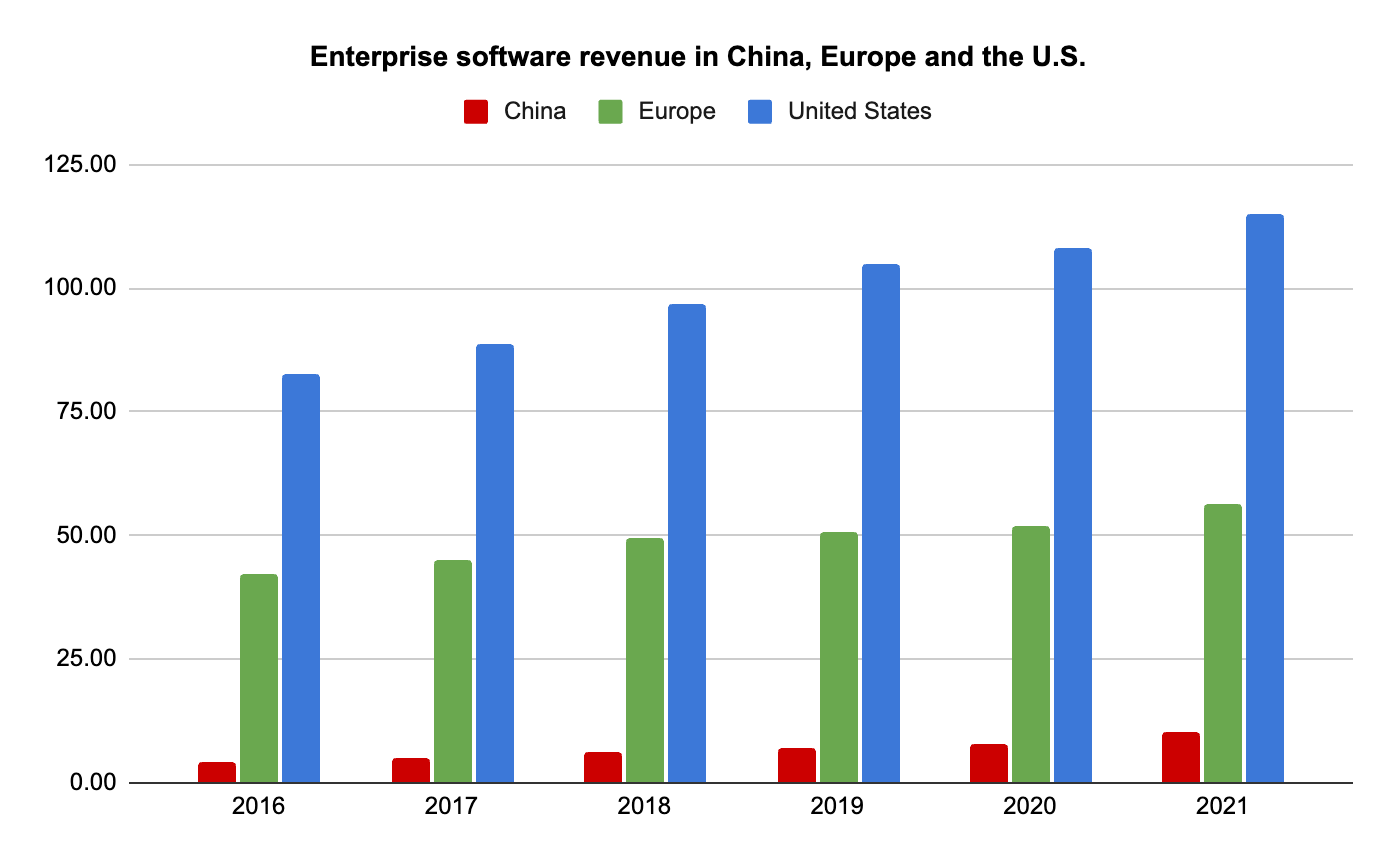

The divergence in AI commercialization between the U.S. and China is, in many ways, unsurprising. China’s digital economy is heavily consumer-driven, dominated by e-commerce, online payments, and social media, while enterprise software—particularly Software-as-a-Service (SaaS)—remains sorely underdeveloped. In contrast, the U.S. has a more balanced mix of enterprise and consumer-facing firms, with globally dominant players on both sides of the enterprise-consumer divide. America’s mature cloud computing sector also means that it is better positioned to commercialize AI through the many enterprise customers already using the cloud.

If AI enhances existing processes, then it makes sense that tech firms in each country would commercialize AI in ways that align with their most profitable business lines. Thus, explaining the divergence in AI commercialization ultimately comes down to understanding how the U.S. and China developed such fundamentally different digital ecosystems in the first place.

Let's start by unpacking why China does not have a robust enterprise software ecosystem.

China’s inherent weakness in enterprise software

A. Industrial Composition

The most effective way to understand this is to look at the demand-side story for enterprise software in the two countries.

What kind of firms benefit from enterprise software? If enterprise software is about driving productivity gains for white-collar workers, then it is most valuable to knowledge-intensive sectors or, more broadly, firms with a predominantly white-collar workforce. This distinction between knowledge-intensive and labor-intensive firms is critical for enterprise software because the economic composition of firms in the U.S. and China differs significantly along this axis.

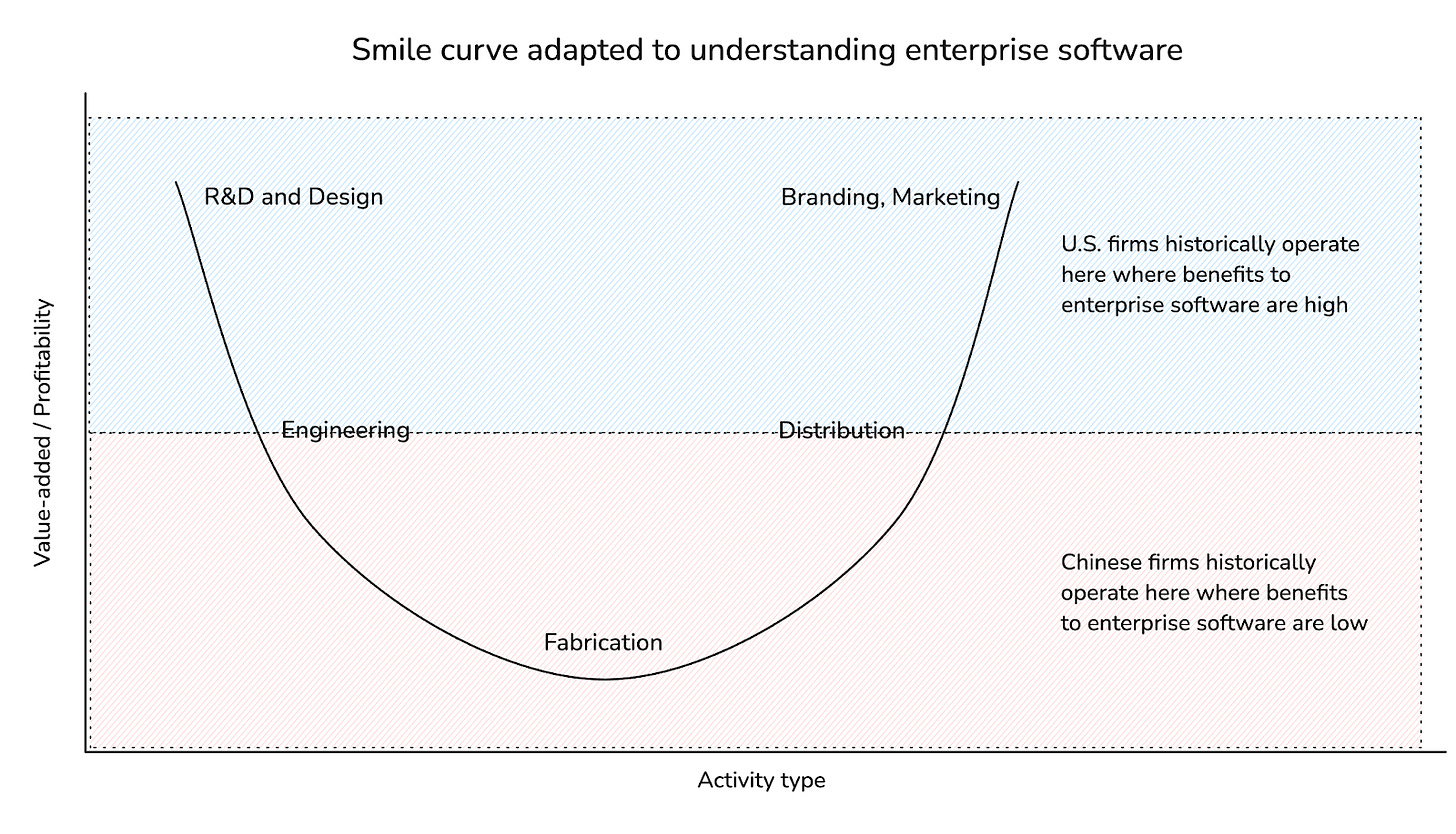

The U.S. has a highly developed knowledge economy, with industries like finance, insurance, and professional services making up a large share of its GDP. Even in traditionally less knowledge-intensive sectors—manufacturing, textiles, hospitality, and food & beverage—U.S. firms tend to dominate the higher-value portions of the industry, focusing on branding, product design, and marketing rather than physical production. They operate at the two high-value ends of the “smile curve” (see graph below), where demand for enterprise software is naturally greater.

The result is that knowledge workers represent a significant portion of the U.S. labor force, with estimates indicating that there are approximately 100 million knowledge workers in the U.S. as of 2023—roughly 60–76% of the total workforce.

In contrast, Chinese firms tend to sit at the bottom of the smile curve, focused on labor-intensive fabrication. Outside of manufacturing, construction and agriculture—also low IT spenders—are top contributors to China’s economy. In these segments, white-collar productivity software has far less impact, resulting in overall resistance to enterprise software adoption.

Another key challenge for less knowledge-intensive sectors in China is the lack of high-quality datasets, which limits business’s ability to use sophisticated enterprise software. Because non-knowledge economy industries have historically underinvested in IT infrastructure and enterprise software, they operate with mostly analog, fragmented, low-quality, or even non-existent datasets.

This lack of digitization creates a major barrier when using enterprise software, let alone the customization of AI models for industry-specific applications. So, even if AI tools were available, firms in these sectors would struggle to adapt them to their workflows, let alone find ways to commercialize them.

B. State-Owned Enterprises

Some estimates also suggest that up to 28 percent of China’s GDP comes from state-owned enterprises (SOEs). SOEs are often subject to stricter data and security regulations that may restrict the use of private-sector technology. And only certain companies have the capacity (or are willing to adjust their business models) to meet these requirements.

As one-third of the economy is driven by the state, it can often move slower, too. One of the key reasons is that there are added bureaucratic practices such as chain reporting and cross-departmental oversight. In theory, the goal is to implement checks and balances to make sure individuals or teams are not misusing governmental resources. In practice, however, this often results in slower processes within these organizations. And as with many government entities, they are slower to introduce new technology, such as software, which is often seen as non-essential.

Finally, jobs are often created by China’s SOEs not for efficiency gains but for social stability purposes. In government-funded firms, it wouldn’t be hard to find people whose jobs are to literally sit on a stool and press the elevator buttons for you. Or patrols sitting in a toll office at an automatic payment parking lot. The point is not to increase efficiency but to create jobs and, thus, enhance social stability.

C. Cheap labor

China’s comparatively cheap labor costs have also created an unwillingness to pay for enterprise software. In sectors with low wages, businesses have less incentive to adopt software solutions that enhance worker productivity, as hiring additional labor is often cheaper than investing in automation or AI-driven tools.

This is particularly evident in industries like retail and customer service, where tasks that might be automated in high-wage economies are still performed manually in China. For example, rather than deploying AI-powered chatbots or automated workflow systems, many companies simply hire more staff to handle routine tasks.

The same logic applies to most back-office functions. While enterprise software in the U.S. streamlines operations and reduces white-collar labor costs, Chinese firms often rely on cheap office labor instead of software solutions. As long as labor remains relatively inexpensive, the financial justification for investing in enterprise software—and, by extension, AI-powered enterprise solutions—remains weak.

D. Irregular, informal workflows

Another major challenge for enterprise software and SaaS adoption in China is the prevalence of informal work processes within many firms. To this day, many professionals still use consumer-facing apps for work, such as WeChat, to communicate with colleagues, transfer files, and run meetings, even though there are existing Slack-like alternatives such as Alibaba’s DingTalk or ByteDance’s Lark that have rich collaborative features.

Part of the reason for this is that the boundaries between work and life are often blurred in Chinese workplaces.1 In the U.S., it would be uncommon to add your colleagues on Instagram or get their phone numbers unless you're actually friends. But in China, everyone is defacto connected on WeChat. This blurring of lines means that employees never quite “log off.” In many workplaces, bosses expect to be able to reach their employees 24/7 (something Grace experienced firsthand when working in China). And not promptly responding to your boss is practically unthinkable for most Chinese workers - given that they know you are always on WeChat and not checking your emails is not an excuse.

From a management perspective, this access to employees can be a competitive advantage since it allows employers to squeeze workers of greater productivity. However, the blurring of work and life also makes it extremely challenging for other software to displace WeChat as the defacto productivity platform.

Unlike in the U.S., where standardized workflows make it easier to integrate software solutions for automation and efficiency, many Chinese companies operate with highly customized or ad-hoc procedures that are difficult to codify into software. Decision-making can often be relationship-driven rather than process-driven, and informal workarounds frequently replace structured workflows. This makes enterprise software far more challenging to adopt, as rigid software solutions struggle to accommodate the fluid, and often informal nature of many business processes in China.

In addition, during the early 2000s in China, pirated software (as well as DVDs and CDs) was so rampant that it became a kind of pseudo-legal operation in the grey area. Small shops blatantly sold pirated software like Word, Excel, and Photoshop. Even legitimate companies would sometimes choose this much more cost-effective option. And where a company employer wasn’t willing to spend on software, individual employees might go out on their own and purchase pirated versions.

Competition in China’s consumer internet

Putting aside China’s lack of competitiveness in enterprise software, Chinese tech firms have largely leaned towards consumer-driven applications—even when it comes to AI—because of the highly competitive structure of its tech industry.

Compared to U.S.-made apps, which focus more on providing specific functions or utility to users as their core mission, Chinese tech giants prioritize capturing and controlling the entirety of a user’s online activity because more activity equals more engagement, which equals more opportunities for monetization.

While their entry point is typically through a single service—WeChat with messaging, Meituan with food delivery, Trip.com with travel—their long-term strategy is to expand their ecosystem and lock users within their digital walled gardens. This is the driving force behind China’s super apps. Where U.S. firms tend to stay in their lane—Uber in transportation, Airbnb in tourism, etc.—Chinese companies continuously integrate payments, social media, live streaming, and now AI chatbots to deepen user engagement and prevent churn.

This intensely competitive environment means that China’s tech giants are constantly vying for market share. Each giant does whatever it can to keep users locked into its ecosystems. When new technology emerges, this urgency is amplified. Each player hops on the bandwagon, fearing that inaction will result in losing users to the competition. [Grace wrote about this phenomenon in her Tencent integrating DeepSeek article.]

In this way, AI is seen as an immediate competitive advantage in the battle for 流量 (traffic/engagement), which remains the central currency of China’s consumer-centric internet economy.

Conclusion

As we’ve shown, China’s inclination to commercialize AI through consumer platforms rather than enterprise software is driven by deeper structural factors, not just a matter of preference. The socioeconomic fabric of the two economies is vastly different. While there has been overlap in innovation and productivity drivers over the last three decades of the consumer internet era, the age of AI is pushing them down distinctly divergent paths.

Why does it matter whether AI is commercialized through existing consumer platforms or enterprise software and SaaS? The answer lies in productivity gains. As with any general-purpose technology—if AI can truly be considered one—the key to its economic impact depends on how widely it is diffused. For AI to drive meaningful productivity growth, it must be adopted broadly across industries, not just concentrated in the hands of a few dominant firms.

In China, where AI diffusion is happening primarily through existing digital platforms, its benefits may remain highly concentrated among the tech giants that control the internet economy. If AI adoption is limited to enhancing consumer engagement rather than improving business operations across sectors, its impact on overall productivity may be minimal.

Even in the U.S., where AI is being commercialized through cloud-based enterprise services, it is still unclear whether adoption will translate into actual productivity gains. The fact that companies are buying AI services from Microsoft, Amazon, and Google signals that they have the capital to invest and are willing to experiment, but whether these investments will drive efficiency improvements or sustained economic transformation remains an open question.

During the notorious one-child policy days, the way to make sure that women—even elite knowledge workers like scientists or officials—were deterred from having a second child was by being told that they would bring shame to their organization/workplace. That was enough to deter most from doing what may have been good for their individual wants. This is so fundamentally different from how individual desires are viewed in the West. Even to this day, in a private company, employees are expected to represent their team or department, thus intensifying the blurring of the boundary between work life and private life.

As a communication scientist I am fascinated by the impact on the communicative expression and interpretation by Chinese professionals who use consumer-facing apps to communicate with colleagues. Your reference to "the blurring of work and life" is most telling in this respect and your observation of the struggle to accommodate the fluid, relationship-driven informal nature of many business processes in China.

Great piece! Have you looked into how investment networks and profitability pressures differ between the U.S. and China? Both countries are pouring hundreds of billions into this space, but the U.S., in particular, will need to recoup much of that investment given that is is led by (arguably) risky private investment with local subsidies vs. China's focus on state telecom-led infrastructure buildout and economic stability. Also, a future thought---if the market commercialization doesn’t deliver strong returns, could the militarization of AI become a way to secure defense funding instead? Would love to hear your thoughts moving forward.